About Kalila wa Dimna:

Talking Animals and Travelling Tales

Dr Rachel Scott

Royal Holloway, University of London and Language Acts and Worldmaking

Stories are the foundation of human society. From the beginning of time, humans have told tales to each other, through words, songs, and images.

Stories travel. They weave their way through the histories of people, places, and times, moving across languages, cultures, faiths, and political borders, and into heart, mind, memory.

Even in stillness, when preserved in the pages of a book, say, there remains in them a quality of dynamism. A potential to do and say and mean so much more than perhaps ever imagined at their moment of origin (however long ago that may be). It is for this reason, perhaps more than any other, that stories live on, continuously finding relevance in new contexts.

Stories entertain and educate, providing a way to understand the world around us. But more than this, beyond offering a glimpse of a past time, another place, or a different perspective, they actively help to create our experiences of this world. Through them people have fashioned their identities, narrated their histories, come to terms with their past, and forged communities of belonging.

If we are the stories we tell, then what do those tales say about us? Or about how humans and societies relate to one another?

If we trace the weft and warp of tales that have travelled, what do they reveal? What connections, or dissonances?

This exhibition and its events explore these questions through Kalila wa Dimna – a book that provides a wonderfully rich example of how stories travel; how they take on different forms and are continuously reinscribed with meaning; and how they enable people to both understand and create the world around them.

About Kalila wa Dimna

Kalila wa Dimna is one of the is one of the most widespread and influential books in the world.

It was written in 750 CE by a Persian convert to Islam named ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Muqaffaʿ (d. ca. 756 CE), who was a poet and courtier to Abbasid caliphs. The book is a collection of moral fables – stories that teach a lesson about how to live or behave in a specific situation. Originally intended to instruct monarchs in how to rule and their counsellors in how to advise, it addresses topics that are universal to human life: how to understand people and situations, how to make friends and deal with conflict, how to gain wisdom, as well as dealing with the consequences of jealousy, pride, and ill-considered action.

Kalila wa Dimna uses storytelling to understand the world and other people, revealing the messy complexity of life, the multiplicity of perspectives and voices that comprise it, and the fact that there exists not one world or truth, but many, and unequal at that.

The book uses a framing technique consisting of a dialogue between a king and his counsellor in which the king poses a series of questions or problems to which the counsellor responds with stories that provide guidance or resolution through positive and negative examples. The stories the advisor tells have more stories embedded within them, told from different perspectives by different narrators. This type of storytelling was an ancient narrative technique used to explore the nature of truth and was commonly found across the world.

Many of the tales’ narrators are anthropomorphised animals who speak and act like humans. The title of the book in Arabic, for example, comes from the names of two jackals who serve in the court of a lion king.

The animals’ actions hold a mirror up to human society and the messy moral complexities of human nature. We, the reader, see ourselves in the events they describe, and can place ourselves in the centre of the action or issue debated. Storytelling then becomes a type of imaginative role play that enables us to test our responses to moral and practical challenges, as well as developing understanding of the world.

Kalila wa Dimna, 16th/17th century CE, Arabic, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cod. arab. 615, folio 28

Kalila wa Dimna, 16th/17th century CE, Arabic, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cod. arab. 615, folio 43

Kalila wa Dimna’s history & origins

Kalila wa Dimna has a long and complex history in world literature.

The book’s origins lie in a Sanskrit work called the Panchatantra (meaning ‘Five Treatises’), which has been dated to the fourth-century CE. This was translated into Pahlavi (Middle Persian) in the sixth century and subsequently Old Syriac, before reaching the Abbasid court in the eighth century, where it was translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ.

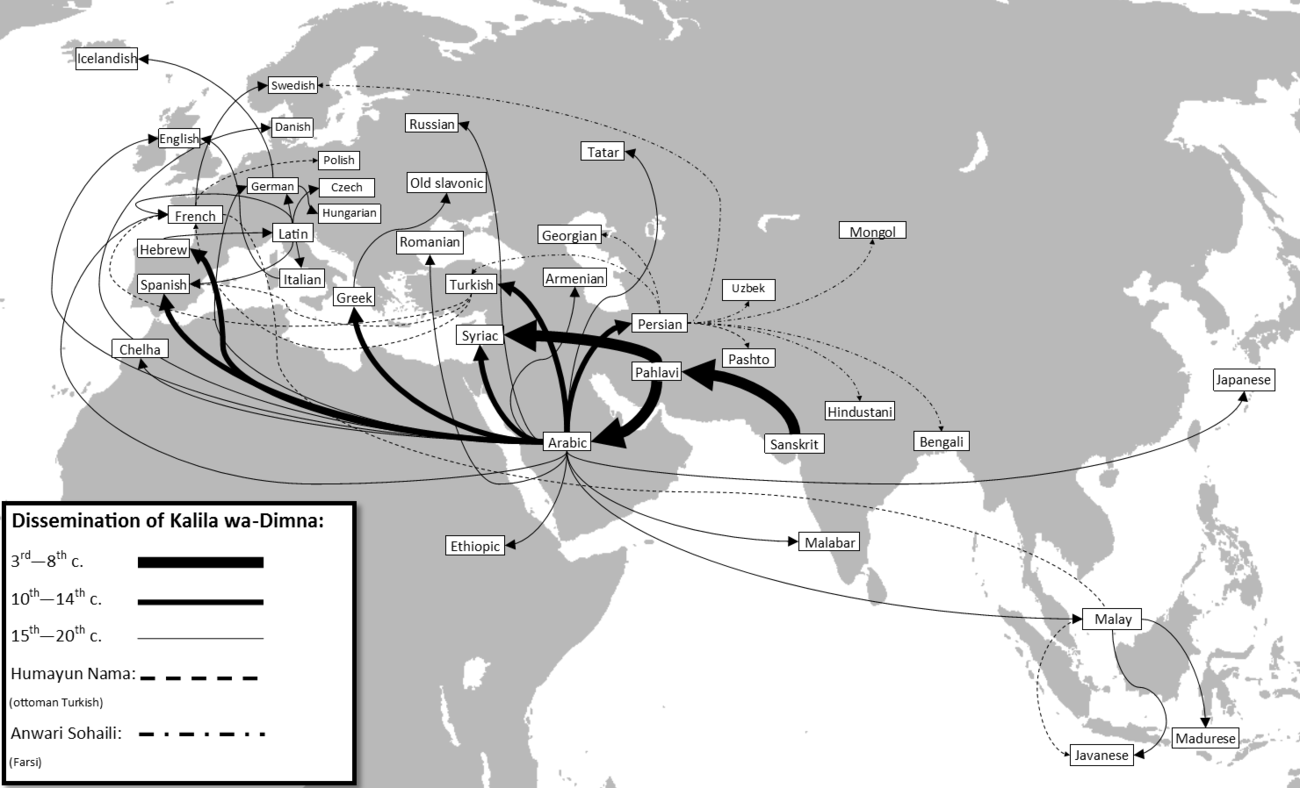

The fables spread widely, following multiple paths of dissemination. They reached northern and western Europe via al-Andalus (the Muslim-ruled lands of modern-day Spain and Portugal). From here the Arabic was translated into Old Spanish and Hebrew, then into Latin, and subsequently into other European languages including Spanish, Italian, German, French to name only several examples.

Over the centuries Kalila wa Dimna has been translated into more than 40 languages and read and re-interpreted almost continuously by different audiences; each time being adapted to suit diverse linguistic, cultural and religious contexts.

This is a book that lives in translation, in a dynamic movement from one time and place to another.

Kalila wa Dimna, 14th century CE, Arabic, The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, MS 578, folio 5r

Map of Kalila wa Dimna’s transmission. This publication has been made possible via the Kalila and Dimna-AnonymClassic research project at Freie Universität Berlin. The AnonymClassic project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 742 635.

Find out more about the AnonymClassic project here.

Kalila wa Dimna: ‘a remarkable document of the history of contacts between civilisations.’

— François De Blois

Indeed, Kalila wa Dimna's transmission offers a glimpse into intercultural exchanges and interactions. It stands as what one critic has called ‘a remarkable document of the history of contacts between civilisations ’ (François De Blois), highlighting the importance of stories and storytelling politically as well as personally.

Many of the translations made across the centuries add new introductions that explain Kalila wa Dimna’s importance, often linking its transmission to the establishment of great civilisations. These introductions often describe it as a ‘jewel’ or ‘treasure’, a precious object to be sought out and appropriated – sometimes through subterfuge, deception, and theft – for the benefits of a people or to claim political legitimacy. Books, then, are never ‘just’ books but instead can become symbols of power, prestige, and knowledge.

Kalila wa Dimna demonstrates the interconnectedness of the world’s cultures: ideas and forms do not materialise out of nothing but are created in dialogue – and often in competition – with other people and other places.

European forms of storytelling owe a great deal to texts that originated in the east. Authors such as Geoffrey Chaucer (The Canterbury Tales), Giovanni Boccaccio (The Decameron), Marie de France (Lais), Jean de la Fontaine (Fables), and Juan Manuel (El Conde Lucanor), who are considered some of the most important writers in English, Italian, French, and Spanish literatures, borrowed the framed narrative technique of embedding tales within tales – and in some cases, appropriated entire stories – from works such as Kalila wa Dimna.

Its impact continues today and can be seen in the plethora of contemporary translations, dramatic adaptations, and visual retellings that the fables have inspired.

Detail from the Exemplario contra los engaños y peligros del mundo (1493), a later medieval translation of the fables from Latin. Biblioteca Nacional de España, INC/1994, folio 16v