The Arts of Storytelling: Kalila wa Dimna in the classroom

A workshop with Sir John Heron Primary School, Newham

led by Dr Rachel Scott, Language Acts and Worldmaking / Royal Holloway, University of London

and Lead Textile Artist Sonia Tuttiett, East London Textile Arts

Over the course of two days in October 2021, Dr Rachel Scott, researcher on Language Acts and Worldmaking and Lecturer at Royal Holloway, University of London (RHUL), and Lead Textile Artist, Sonia Tuttiett from East London Textile Arts (ELTA) ran Kalila wa Dimna project workshops for year 6 pupils at Sir John Heron Primary School in Newham, East London.

The workshops covered multiple areas of the curriculum: literacy, languages, art and design, and elements of PSHE (Personal, social, health and economic). Our purpose was multiple: to engage children with questions of cross-cultural encounters using Kalila wa-Dimna as a starting point; to explore issues of identity, community, and migration; to get them engaged with languages in a fun way, and utilising knowledge of any home languages; and to give them an opportunity to get creative and make works of art that will be shown in the exhibition at the P21 Gallery alongside the work of professional artists.

This was important to us, as Newham is a borough with very little formal provision for engagement with the arts through galleries and museums, and because children in this multicultural and multilingual borough do not often get an opportunity to ‘see’ themselves or their cultural heritage in the London cultural sector, or to ‘take up space’ in this world.

15 children from year 6 (10-11 years old) took part: Sulaiman, Liyana, Saffiyah, Khizar, Fairin, Jamilah, Imtiaz, Tahmid, Zubair, Zainab, Lakhbir, Mobinal, Eliza, Tanzila, and Megy. They were lively, engaged, and creative. A joy to work with.

While many of the children spoke languages other than English at home or had learned English as a second language after migrating to the UK, it was interesting to note that very few used their home languages to engage with literature. Instead, they were used in practical circumstances – to communicate with family or, in some cases, to support parents or other family members in formal settings, such as when interacting with local councils or services. For nearly all of the children their first reading language was English, a factor that also meant many of the children did not habitually read with parents but instead with siblings, cousins and friends. As a result, the school strives to promote reading and literacy and the school building itself is designed to maximise pupils’ engagement, with dedicated ‘reading corners’ featuring cosy seats and plenty of books dotted throughout the grounds (even outdoors). That SJH understands and promotes the value of cross-cultural understanding and learning through literature, history, and the arts is demonstrated by the displays of pupils’ work engaging with literature and arts from cultures across the world.

Over the two workshops, it became clear that many of the pupils had a real interest in languages and enthusiasm for language learning: some shared how they had been reading books in other languages independently – using graphic novels to learn Japanese, for example, or working their way through stories in German, French, and Spanish by themselves with the help of a dictionary or Google Translate. In addition to getting the children engaged in the visual arts, we wanted to encourage them to see language – whether English, their home language, or another foreign language they were learning independently – as a source of creativity and fun too.

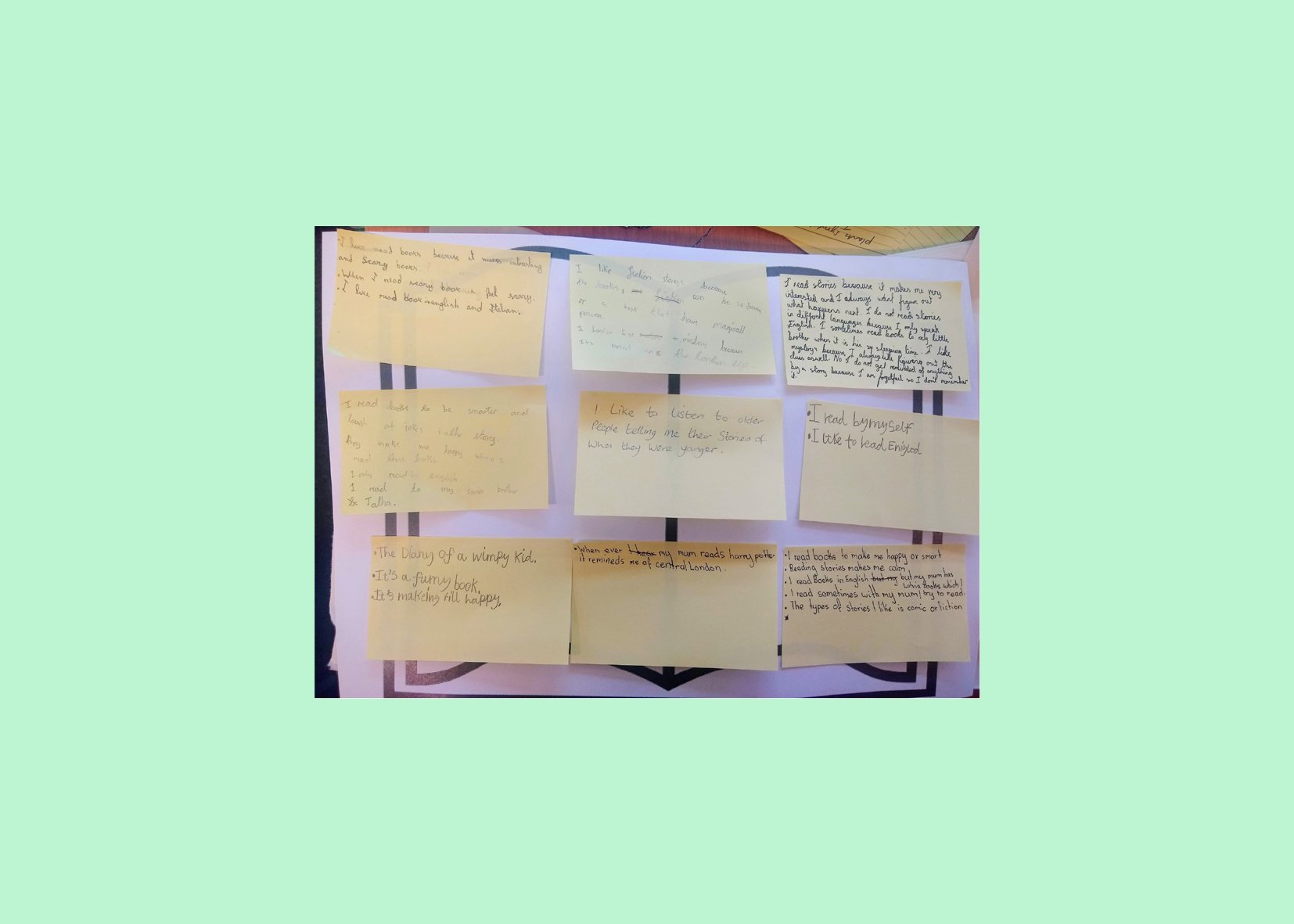

In the first workshop, we began by talking about the importance of storytelling and thinking about why we read and tell stories, how stories can help us to feel connected to other times, places, and people and experience other ways of living and being. As a warm-up exercise the children wrote down their thoughts on post-it notes to create their own ‘story of stories’ (see the images below), sharing their own experiences of storytelling and reading – who with, in what languages, and the feelings it evokes.

After the warm-up exercise, we talked about how stories travel, for example with people when they move from one place to another, through families, across languages and times. I introduced Kalila wa-Dimna and explained its origins (Indian, Persian, Arabic) and journeys from East to West and influence on European authors and described what it was about. We also looked at some of the paintings from medieval and early modern manuscripts to see how words and images interact and how they aid understanding.

We then read one of the book’s fables, ‘The Tale of the Four Friends’ – a story about looking beyond perceived differences, working together to overcome adversity, and finding community and a sense of ‘home’, which offers a fruitful way of exploring issues of identity, community, and migration. We discussed the story’s themes, characters, and meaning, as well as about the importance of acknowledging the positive aspects of difference, and about how communities and a feeling of ‘home’ can be created – themes that we picked up on in the second workshop.

Practising skills in close reading and working in groups, the children used the four animal characters (mouse, crow, turtle and deer) as starting points for thinking about the importance of looking beyond apparent differences to find common ground and build community. Building on our discussions of words and images, we asked the children to work in groups to create a calligram of one of the characters using terms that came up in their discussions (see below for some of their responses). They thought carefully about the design, playing with size, shape, and style; freeing the words from the page of the book and using them to represent their ideas about the text’s themes visually.

After a break, it was time to get creative with an activity that allowed the children to bring their own personal experiences and perspectives to the topics discussed in the morning.

Sonia introduced the children to a variety of textile patterns, art forms, and symbols from across different cultures, as well as showing them images from the medieval manuscripts in Arabic, Turkish, Persian, and Old Spanish. We asked them to design ‘paperchain’ dolls – figures connected to each other to highlight how individuals, societies and cultures are interconnected and interdependent.

The children’s responses were inspired. The last part of the workshop was a hive of creative activity, with the pupils researching textile patterns and symbols and planning the design of their pieces, thinking about style, placement, and the relationship between text and image.

What was encouraging to witness was their interest and enthusiasm for languages. By the end of the session, many of the children had begun to translate some of the key terms from our discussions into other languages, both those they spoke at home (Urdu, Pashto, Bengali) and those they had an interest in (German, Korean, Japanese).

The figures produced by the children, mounted individually on colourful felt by Sonia to allow for different combinations for the on-ground exhibition installation (Courtesy of Sonia Tuttiett).

Between the two workshops we set the children tasks to do at home (with the teachers’ support). The first was to continue translating words related to any of the key ideas and themes we had been discussing (e.g. ‘friendship’, ‘community’, ‘home’), which they could then use as part of their designs for the ‘paper dolls’. And the second, to explore the stories that have either travelled with or through their own families or have been important to them, we asked pupils to get a member or their family to tell them a story, fictional or fact.

The kids responded enthusiastically, with many recording brief audio summaries of the stories told to them by their friends and families in class with their teacher. These recordings will be used by the school in a display on storytelling and the fable, as part of their drive to encourage literacy and reading at home.

In the second workshop, the children continued working on their creative responses to the fable and our discussions the previous week, with Sonia’s help. Many of their designs featured words that were important to them in a range of languages; many pupils also used visual arts familiar to them from their heritage as inspiration – such as Pakistani truck art or Latvian textile patterns – as well as cross-cultural symbols of friendship. Sonia was impressed with the children’s creativity, how quickly they picked up new skills in stitching and painting, and their ability to create coherent and visually striking designs in such a relatively short space of time.

The final peices of artwork are on display in the P21 Gallery throughout the exhibition.

Our concluding activities returned to the creative potential of words and languages. We talked about how languages can create as well as reflect experiences of the world that are different for each individual and, building on recent work the students had been doing about poetry in class, did an exercise in creative writing inspired by the ‘Tale of the Four Friends’ and its themes. After coming up with collective definitions of the fable’s themes – abstract nouns like ‘friendship’, ‘home’, ‘community’, ‘migration’ – I tasked students with writing a short piece of prose or poetry that explored their own personal experiences of one of them in concrete terms, focusing on sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste.

At first, the pupils were hesitant, worrying about getting it ‘wrong’. But with encouragement and through talking about other examples and different styles of writing, they produced pieces that were highly personal, funny, touching and moving, and which showed evidence of real creative thinking.

A couple of examples can be found below.

Home to me is Keshiki.

Home to me is Ai.

When I cry,

someone makes me full of pride.

When I am frustrated,

someone makes me creative.

When I am hungry,

I am fed food that’s lovely.

“Thanks!” I yell with excitement,

pretending I’m a hero and holding onto the moments.

Home to me is Keshiki.

Home to me is Ai.

Now I don’t cry

Now I’m not frustrated

Now I don’t moan when I’m hungry,

because I love home and the people in it.

Sulaiman

Hearing the birds chirping, smell of pizza. Hearing football bouncing, seeing the Leaning Tower of Pisa and seeing other famous buildings in this country. Watching Peppa Pig in the bright sun. Showing my toys to my friends in a white school. Having friends there to play with. My family in the light, helping me from dangerous things. Bigger brother looking at the solar eclipses. Me and my family playing with snow having snow fights in the cold. Seeing diminutive ants and microscopic bees. I used to be scared of them, not anymore. I was willing to go to France but we missed our flight so we need to go to England.

Anonymous

Feedback about the workshops was highly positive.

93% of pupils rated the workshops as ‘excellent’ and described them as ‘fun’, ‘creative’, ‘amazing’, and ‘joyful’

100% of the pupils said that they had made them think differently about how to be creative with languages

85% that they made them want to explore different art forms

And 93% to explore more stories from around the world

Students also commented on how the workshops had given them an opportunity to be more creative with visual and material arts and languages that they wouldn’t otherwise have, with comments including:

‘I enjoyed the textiles because it’s very fun’

‘I really enjoyed it because I got to be creative’

‘I really liked making the figures and writing in different languages’

‘I learned a new story and new words’

We would like to thank the year 6 pupils of Sir John Heron – Sulaiman, Liyana, Saffiyah, Khizar, Fairin, Jamilah, Imtiaz, Tahmid, Zubair, Zainab, Lakhbir, Mobinal, Eliza, Tanzila, and Megy – for their participation, their energy, creativity, humour and the sheer joy of art and languages that they shared. And also to thank the teaching staff who supported the workshops: Cecilia Bekker and head teacher Vicky Broughton.

The ‘Arts of Storytelling’ workshops were supported by funding from Language Acts and Worldmaking and Arts Council England, as well as the Centre for Visual Cultures at Royal Holloway, University of London.